Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

US Environmental Protection Agency

Environmental Justice: in the context of Sidaway Bridge (Cleveland, Ohio)

“It still spans Kingsbury Run, connecting Cleveland’s Kinsman Road neighborhood to the city’s historic Jackowo Polish neighborhood. But no one uses the Sidaway Bridge anymore. Not since the 1966 Hough Riots when someone tore out planking from the walkway and attempted to set the bridge on fire. Shortly afterwards, Cleveland officials closed the bridge, and for fifty years it has waited patiently to resume its original purpose of bringing the people from these two neighborhoods together, rather than continuing to keep them apart.”

(Cleveland Historical, Sidaway Bridge, Danielle Rose, Jim Dubelko)

01/16/2020

1: The 5 W’s

Environmental Justice is a movement that focuses on unequal distribution and accessibility of resources, and exclusion from community facilities because of poverty, prejudice, race, income, or other marginal status. As landscape architects, we frequently (knowingly or unknowingly) design spaces that sustain this unequal treatment. To work for justice, we must educate ourselves on the social impact of what we do.

I chose the Environmental Justice professional practice network because the social impact of design reverberates, affecting people and communities for years to come. My possible senior project location is the Sidaway Bridge in the Kinsman neighborhood of Cleveland, Ohio. Cleveland has a bitter history with both racial conflicts and segregation, and environmental problems from the heavy industry there. As a culturally-focused project, I’d like to have an understanding of what this community is grappling with and how one project could get the wheels of change turning. Identifying how people in the Kinsman neighborhood have been marginalized will help me work to create a design that helps remedy and acknowledges the truth of our past.

One resource ASLA’s Environmental justice professional practice network led me to was an EPA tool called ejscreen (https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen). It can help identify common environmental justice factors (including demographics and and environmental factors). They will also notify you if any site near your selected location or block group is reporting to the EPA (such as superfund sites or hazardous waste treatment). While ejscreen should not be used for decision making or to label any place as an ‘environmental justice site’, it provides a tool for any person or agency to see the vulnerability of a community. I tried putting the exact location for the Sidaway Bridge and got a PDF report. It uses GIS software and census block group data, so it is a good tool for looking at a comprehensive view of a focus area, and can give leads to follow for future research.

02.11.2020

2: 2 Sides of a Coin

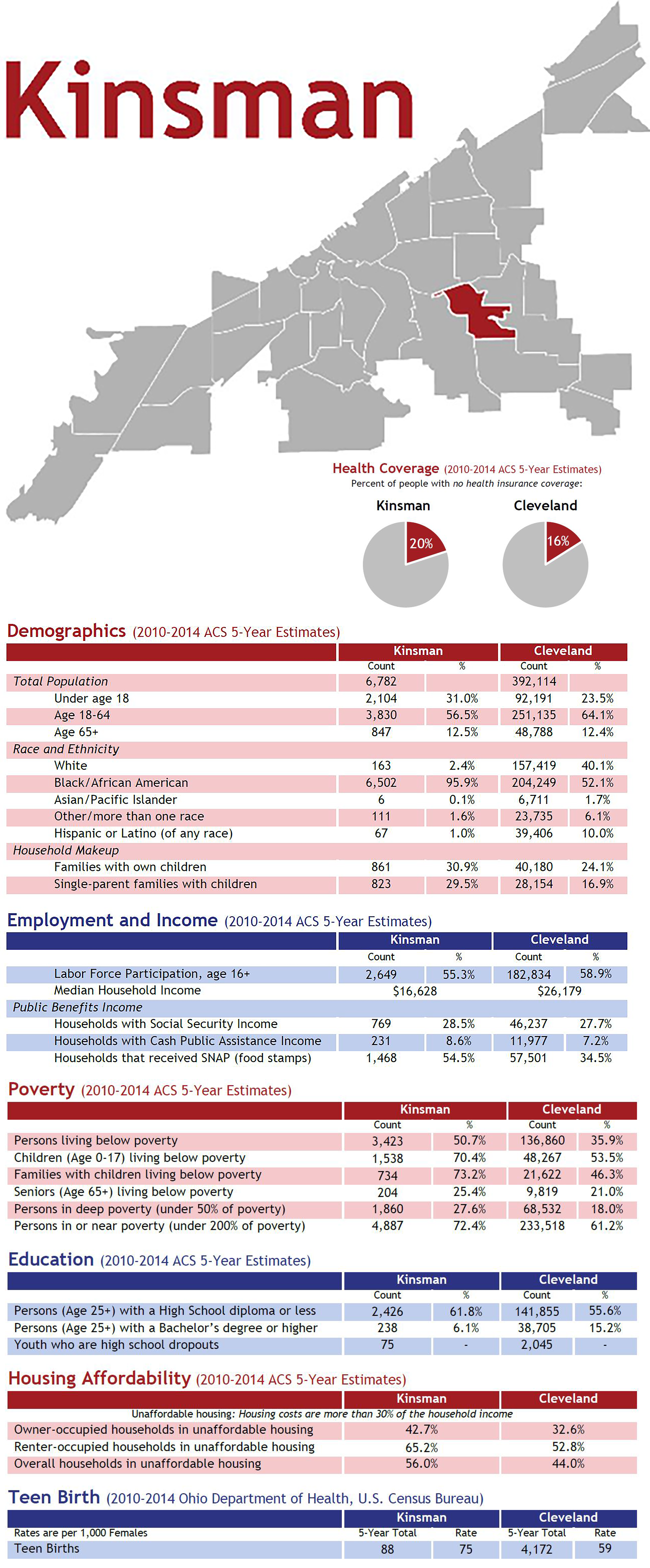

Upon further research I discovered that the EJ screen resource was not well updated, hard to understand, and difficult to verify. The only information that is actually linked is the environment the environmental justice screen by the EPA which I have found is not a valuable source for me or my project. Because of this I have taken to some of my own research in helping me with the topic of environmental justice. I have found data on the two disparate neighborhoods of Broadway-Slavic Village and Kinsman. I have compiled my data and would like to study the two census tracts (and neighborhoods) that lay immediately on either side of the bridge, as well as Cleveland as a whole. Community Solutions is a Cleveland-run site and has information compiled from the American Community Survey and Census on each Cleveland neighborhood compared to the city. I got two snapshots of the neighborhoods on either side of the bridge.

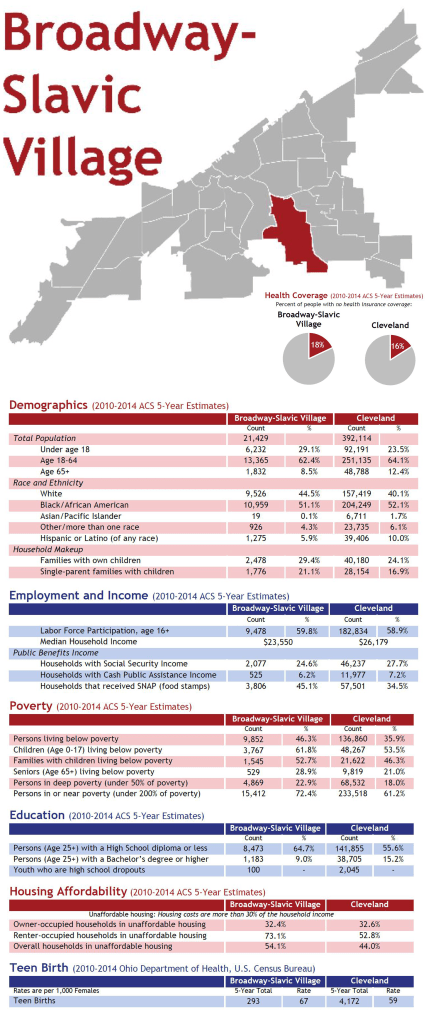

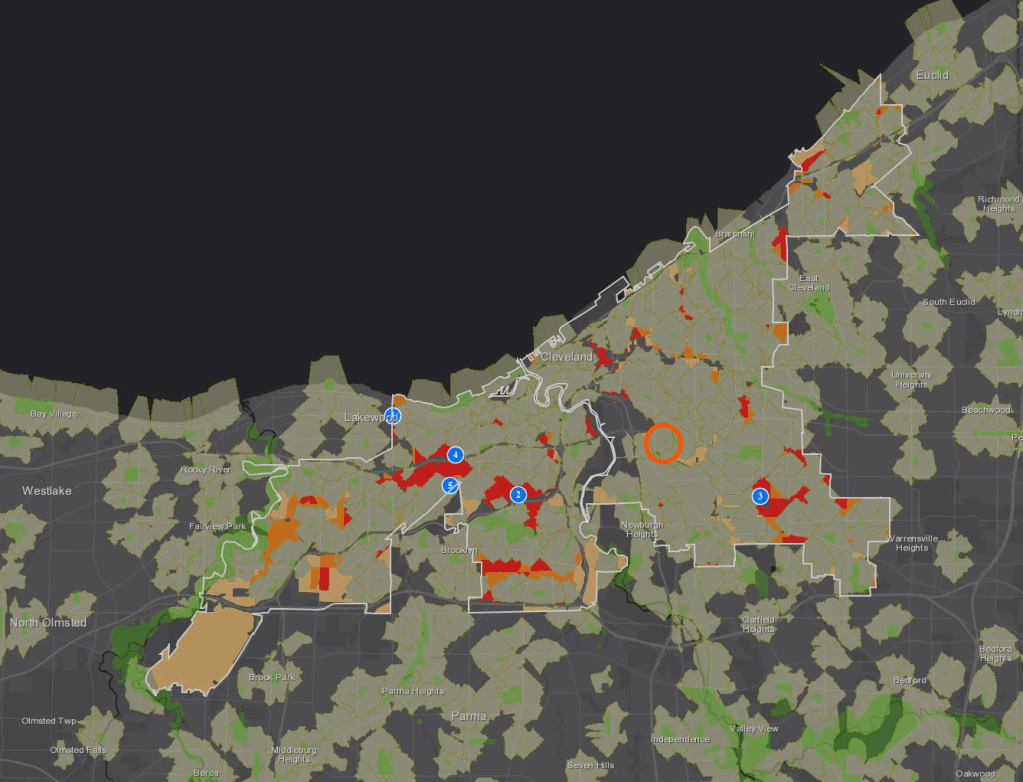

Because data is difficult to find or is unknown for environmental factors of geographies, I instead focused on CDC’s Social determinants of health. To help with identifying demographic characteristics of the Kinsman/Broadway-Slavic Village neighborhoods of Cleveland, I decided to look up environmental factors, demographic factors, and other characteristics that are descriptive of environmental justice vulnerable populations. The CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index map helped me get a better idea of what the neighborhoods are dealing with compared to their surroundings.

dark blue= most vulnerable, yellow= least vulnerable, orange circle=s ite location

the census tracts had vulnerability indexes in the 72nd (Broadway) and 96th (Kinsman) percentile (moderate to high vulnerability).

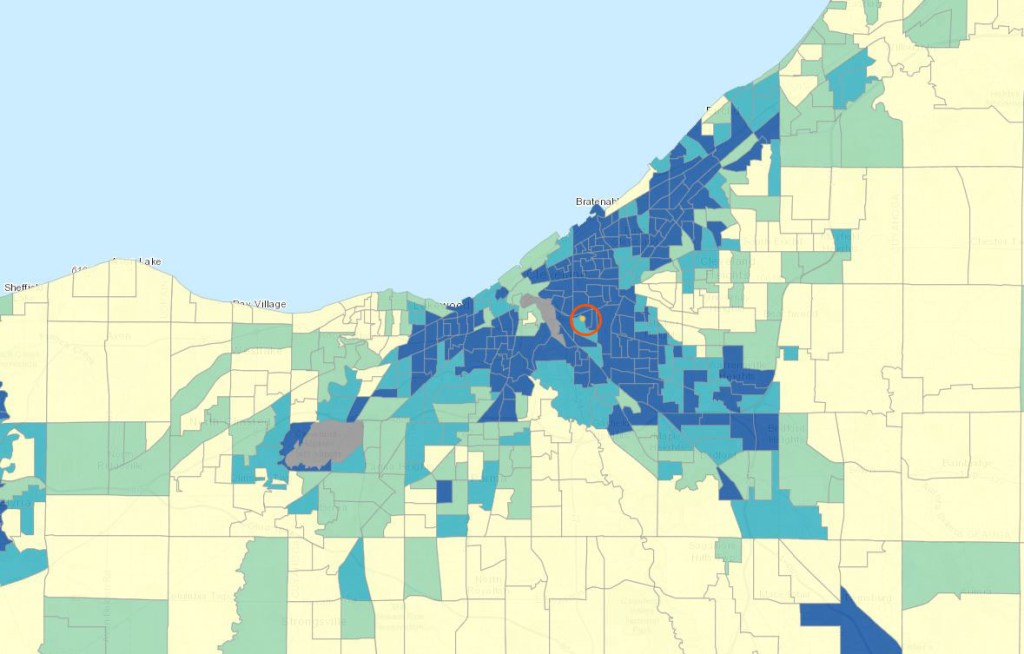

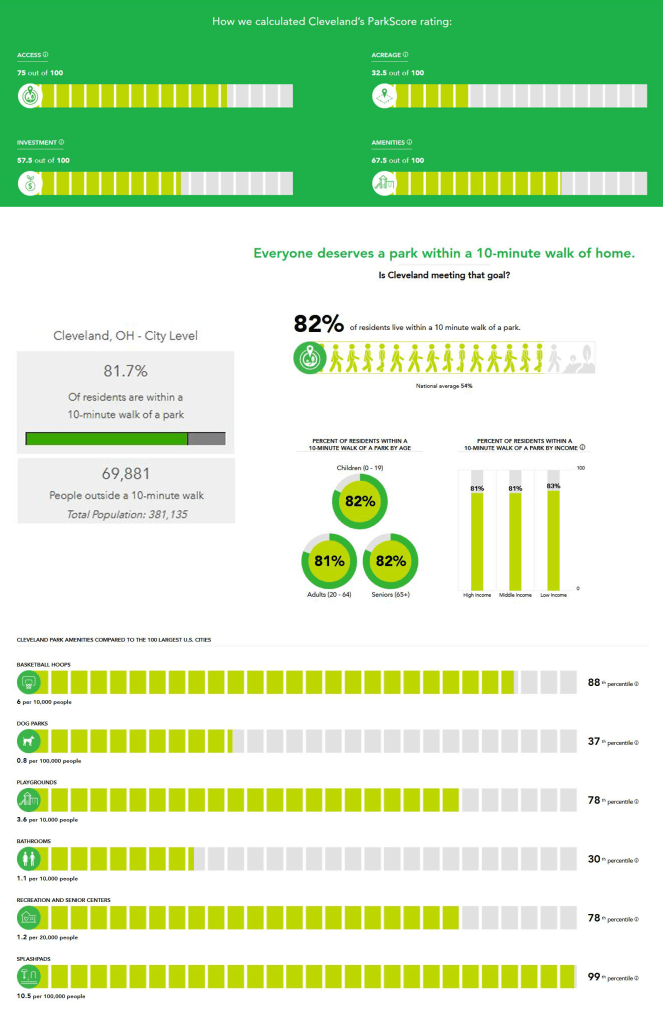

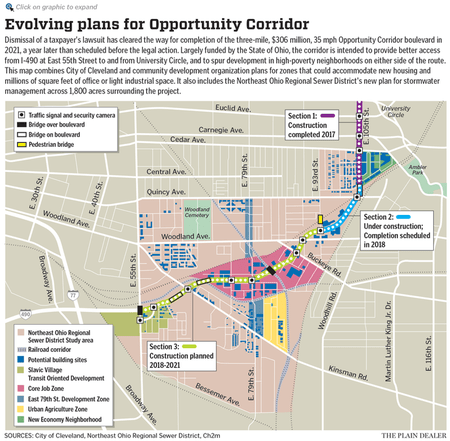

In addition, for information on Cleveland as a whole, ParkScore gave a descriptive snapshot of the city. At ASLA 2019 San Diego one presentation discussed the use of ParkScore in their project. Park Score rates the quality of mid-large cities’ green space across the country based on access, investment, acreage, and amenities.

Red= high park need, olive= low park need, blue numbers= recommended future park locations, orange circle= site area

Creating a demographic profile will help me to figure out who I’m designing for and who are the users of this bridge will be I will. I will do demographic studies on the communities on either side of the bridge to see the differences and communities were dealing with, because a deep issue within the bridge itself was that there is quite a divide between these neighborhoods. Studying it over time might be beneficial as well.

Cleveland is in the midst of an Opportunity Corridor project that is close to our site. This could significantly affect the neighborhood in coming years and is something to pay attention to/ incorporate into the design. Being able to incorporate my site into a larger Improvement plan through the city of Cleveland would be helpful. At the end of the day I have used these tools to find out what the community is currently like so I can better assess what is needed, and will eventually move from research to analysis.

02.19.2020

3: Connecting the Dots

… a closer look at Kinsman

I was going to spend today looking into the history of each neighborhood. But I got side tracked by the trove of information I found on the Kinsman neighborhood. The broad picture is Cleveland was struggling in the postwar years.. or what Cleveland historians like to call the “decline and comeback: 1960-1990”. I will focus on the decline because I would argue Cleveland is still in the midst of its ‘comeback’ as we speak.

The Great Migration brought thousands of African Americans into Northern cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland seeking employment and escaping the violence and segregation of the South. This quickly led to white flight and blatantly racist housing practices that forced Blacks along with many ethnic Americans to live in slums. And let it be known that Cleveland is no stranger to racist planning practices. The 1926 landmark discriminatory zoning supreme court case Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co. kicked off a wave of legally segregated zoning and redlining across the nation.

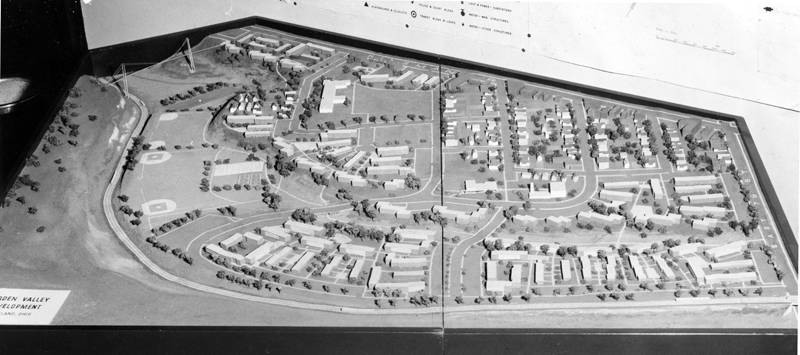

The Cleveland Memory project is a database collection of primary sources that have been archived or donated throughout the years. It is housed at the Michael Shwartz library at Cleveland State University. Much of my records come from this detailed collection of sources because much of what I am looking for was probably considered not worth saving at the time. Cleveland: City on Schedule was a 30 minute film made in 1962 by the Cleveland Development Foundation about the challenges facing Cleveland in Cleveland their steps to solve them, specifically through planning and urban renewal.

If you watch it, you will see that the film hits strangely close to home, discussing the Garden Valley housing development that was built directly next to the Sidaway bridge. Just a few years after the Kingsbury run landfill was built adjacent to the housing development. Meanwhile, the highway act was in the process of deciding the locations for future expressways.

The idea that a bunch of men in offices get to decide to raze whole neighborhoods and communities (or ‘slums and blight’) is infuriating. And instead of being compassionate and finding integrated solutions- mass housing is built. The result of this restructure and renewal is, at the lightest, a human rights violation, and at the most severe, has crippled generations of Americans in a cycle of poverty and helped feed if not create the prison industrial complex, the formation of the modern gang, and police brutality.

“In twenty years, Cleveland envisions a slum-free city. These new communities stand as monuments to what can be accomplished when business and government work together for a common goal”

Chet Huntley, Cleveland: City on Schedule. 1962.

Business and government work together… People was the missing link. Cleveland, nor most US cities, factored in the human beings that were their subjects into consideration. Urban renewal in Cleveland had lofty goals of making Cleveland slum-free by 1980. This leads us to Cleveland today, a city where 36.2% of residents live in poverty, 18.2% in abject poverty, and consistently ranks near the top of US crime and murder rates. Maybe it’s time to admit we did something wrong.

And if you’ve done that, what can you do now? (Coming next week).

03.03.2020

4: Touch Down

In the spring of 2018 I visited Detroit, Michigan with a few other classmates from the College of Architecture and Environmental Design and was led by a professor who grew up in Detroit. We visited multiple firms, non profits, and community-created non-professional sites, and spoke to community members; with the goal to understand different approaches to the site-specific problems Detroit faces. This is when I first began to understand the power of community engagement as a tool in designs.

http://www.designandemotion.org

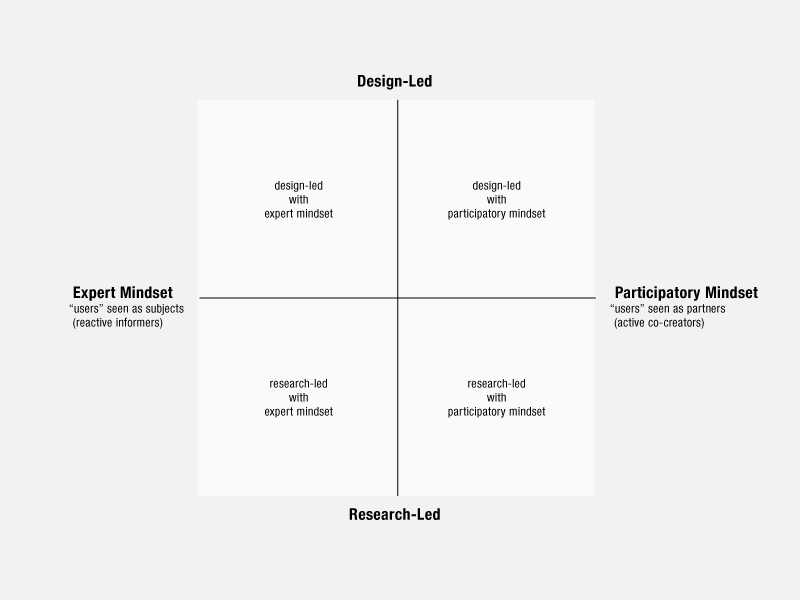

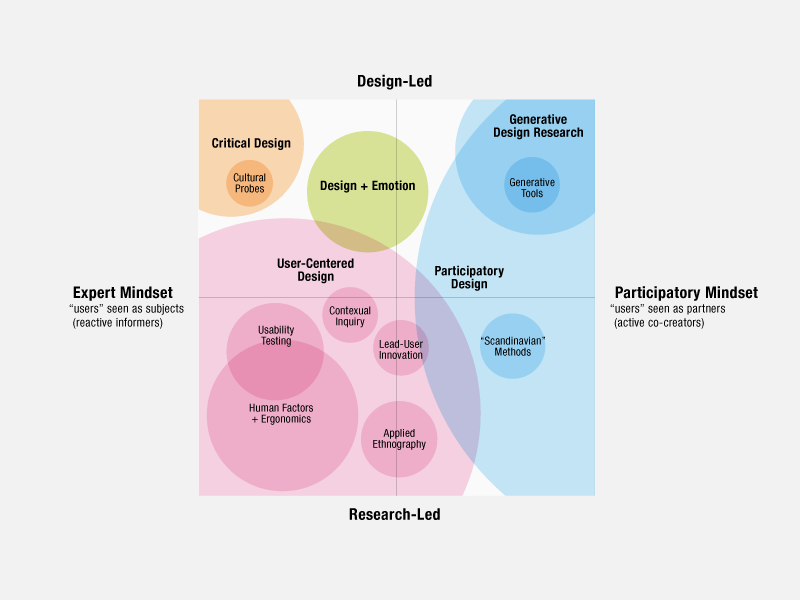

Participatory design (also known as cooperative or co-design) is a process in which a designer actively involves all stakeholders in a design process. But it wont work unless designers truly understand themselves- their role, societal position, and biases.

“Once we are clear on who we are, we can see our position in society relative to the cultural and economic context of the community in which we plan to work. This in turn equips us with empathy rather than sympathy. This distinction is important because designers can find themselves in communities with acute needs that have been repeatedly ignored. Although providing technical assistance to a community in need is a critical role of participatory design, responding with sorrow or pity hampers one’s effectiveness. Sympathy, even when its grounded in understanding, can subtly convey to residents that only the designer’s expertise counts. Another pitfall lies in creating a patronizing process that diminishes the community’s self-worth.” For the editors, only fully self-aware designers can succeed at this work. Furthermore, designers who come in as arrogant experts risk doing real damage”

Design as Democracy: Techniques for Collective Creativity,

David de la Pena; Diane Jones Allen, ASLA; Randolph T. Hester, Jr, FASLA; Jeffrey Hou, ASLA; Laura J. Lawson, ASLA; and Marcia J. McNally

As my project would not be a literal project, community engagement in its fullest would not be feasible. To work with this I have tried to develop a deep understanding of the history of the area and what people face, but I do not know the people themselves, a key part of any engagement process.Since I cannot speak to users and neighbors, I won’t have that vital information. I can create a flowchart with possible questions and answers, culminating in different designs. This is far in the future. But the flowchart idea would allow me to mimic the process of engagement without actually reaching out to people in false pretenses.

Understanding the questions to ask means I need to go back to square one. My goal isn’t to design for people but to design with them. Which means I need to rethink everything and keep an open idea- be ready to accept that everything I was thinking of could be something that users don’t want or need, and could even be harmful. Do you want the bridge reconnected? The question if the communities even want a direct link to one another is valid- a volatile relationship has existed between Slavic Village and Kinsman for generations. Exploring possibilities, understanding myself, developing routes, looking for case studies, and researching community engagement in practice is my next step.

EJ Resources:

- EJSCREEN: https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen

- EPA: https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice

- ASLA PPN Blog: https://landscapearch-environmentaljustice.weebly.com/resources.html

- A Student’s Guide to Environmental Justice: https://www.asla.org/2018studentawards/493806-A_Students_Guide_To_Environmental_Justice.html

- ASLA: https://www.asla.org/justiceresources.aspx

- The Field: https://thefield.asla.org/2019/08/13/environmental-justice-survey-findings/

- The Trust for Public Land ParkScore: https://www.tpl.org/parkscore

- Center for Disease and Control: Social Vulnerability index: https://svi.cdc.gov/

Sidaway Bridge Resources:

- Architectural Afterlife: https://architecturalafterlife.com/2019/01/31/sidaway-bridge-hough-riots-and-the-cleveland-torso-murders/

- Cleveland Historical: https://clevelandhistorical.org/items/show/762

- The Cleveland Memory Project: http://images.ulib.csuohio.edu/cdm/search/field/subjec/searchterm/Sidaway Avenue Bridge

- Community Solutions: Cleveland Neighborhood Fact Sheets: https://www.communitysolutions.com/resources/community-fact-sheets/cleveland-neighborhoods-and-wards/

“Bridge Closed” sign and barricade on the Sidaway Bridge blocking the entrance on the bridge, Cleveland Memory Project, 1976